Contents

Preface

Biases: An Introduction

Book I: Map and Territory

A. Predictably Wrong

1. What Do I Mean By “Rationality”?

2. Feeling Rational

3. Why Truth? And . . .

4. . . . What’s a Bias, Again?

5. Availability

6. Burdensome Details

7. Planning Fallacy

8. Illusion of Transparency: Why No One Understands You

9. Expecting Short Inferential Distances

10. The Lens That Sees Its Own Flaws

B. Fake Beliefs

11. Making Beliefs Pay Rent (in Anticipated Experiences)

12. A Fable of Science and Politics

13. Belief in Belief

14. Bayesian Judo

15. Pretending to be Wise

16. Religion’s Claim to be Non-Disprovable

17. Professing and Cheering

18. Belief as Attire

19. Applause Lights

C. Noticing Confusion

20. Focus Your Uncertainty

21. What Is Evidence?

22. Scientific Evidence, Legal Evidence, Rational Evidence

23. How Much Evidence Does It Take?

24. Einstein’s Arrogance

25. Occam’s Razor

26. Your Strength as a Rationalist

27. Absence of Evidence Is Evidence of Absence

28. Conservation of Expected Evidence

29. Hindsight Devalues Science

D. Mysterious Answers

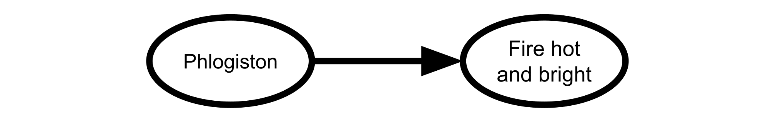

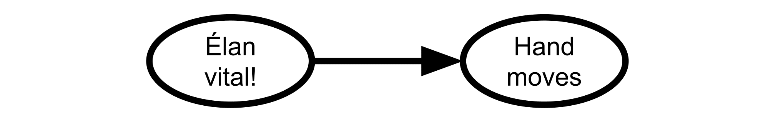

30. Fake Explanations

31. Guessing the Teacher’s Password

32. Science as Attire

33. Fake Causality

34. Semantic Stopsigns

35. Mysterious Answers to Mysterious Questions

36. The Futility of Emergence

37. Say Not “Complexity”

38. Positive Bias: Look into the Dark

39. Lawful Uncertainty

40. My Wild and Reckless Youth

41. Failing to Learn from History

42. Making History Available

43. Explain/Worship/Ignore?

44. “Science” as Curiosity-Stopper

45. Truly Part of You

Interlude: The Simple Truth

Book II: How to Actually Change Your Mind

Rationality: An Introduction

E. Overly Convenient Excuses

46. The Proper Use of Humility

47. The Third Alternative

48. Lotteries: A Waste of Hope

49. New Improved Lottery

50. But There’s Still a Chance, Right?

51. The Fallacy of Gray

52. Absolute Authority

53. How to Convince Me That 2 + 2 = 3

54. Infinite Certainty

55. 0 And 1 Are Not Probabilities

56. Your Rationality Is My Business

F. Politics and Rationality

57. Politics is the Mind-Killer

58. Policy Debates Should Not Appear One-Sided

59. The Scales of Justice, the Notebook of Rationality

60. Correspondence Bias

61. Are Your Enemies Innately Evil?

62. Reversed Stupidity Is Not Intelligence

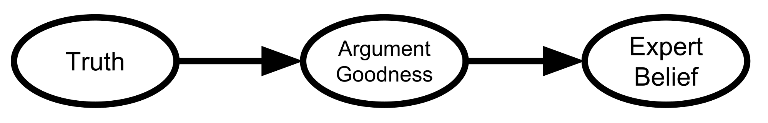

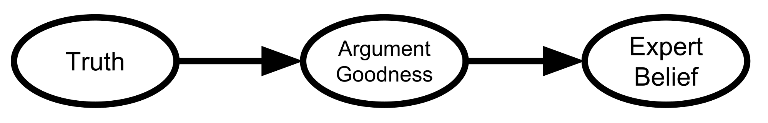

63. Argument Screens Off Authority

64. Hug the Query

65. Rationality and the English Language

66. Human Evil and Muddled Thinking

G. Against Rationalization

67. Knowing About Biases Can Hurt People

68. Update Yourself Incrementally

69. One Argument Against An Army

70. The Bottom Line

71. What Evidence Filtered Evidence?

72. Rationalization

73. A Rational Argument

74. Avoiding Your Belief’s Real Weak Points

75. Motivated Stopping and Motivated Continuation

76. Fake Justification

77. Is That Your True Rejection?

78. Entangled Truths, Contagious Lies

79. Of Lies and Black Swan Blowups

80. Dark Side Epistemology

H. Against Doublethink

81. Singlethink

82. Doublethink (Choosing to be Biased)

83. No, Really, I’ve Deceived Myself

84. Belief in Self-Deception

85. Moore’s Paradox

86. Don’t Believe You’ll Self-Deceive

I. Seeing with Fresh Eyes

87. Anchoring and Adjustment

88. Priming and Contamination

89. Do We Believe Everything We’re Told?

90. Cached Thoughts

91. The “Outside the Box” Box

92. Original Seeing

93. Stranger than History

94. The Logical Fallacy of Generalization from Fictional Evidence

95. The Virtue of Narrowness

96. How to Seem (and Be) Deep

97. We Change Our Minds Less Often Than We Think

98. Hold Off On Proposing Solutions

99. The Genetic Fallacy

J. Death Spirals

100. The Affect Heuristic

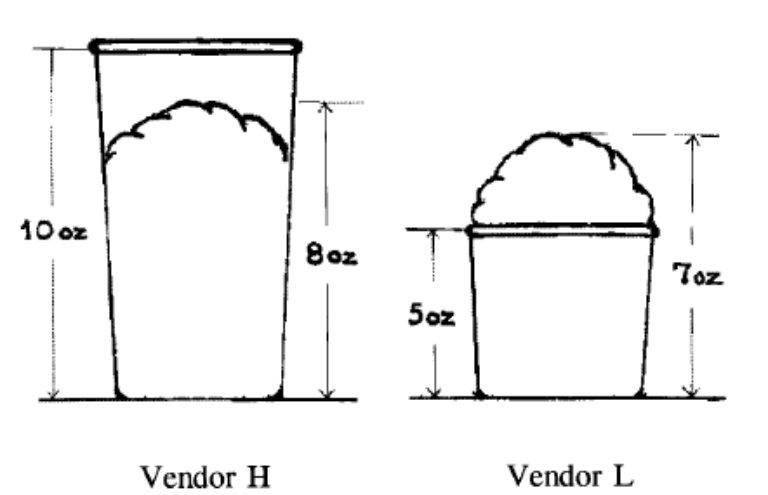

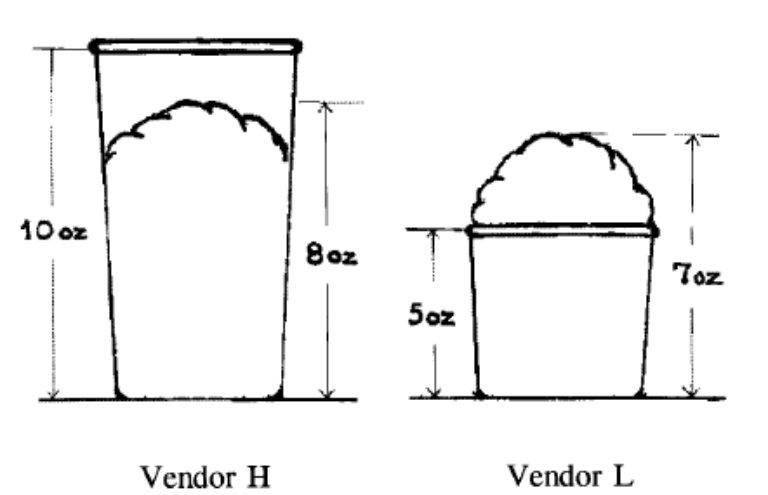

101. Evaluability (and Cheap Holiday Shopping)

102. Unbounded Scales, Huge Jury Awards, and Futurism

103. The Halo Effect

104. Superhero Bias

105. Mere Messiahs

106. Affective Death Spirals

107. Resist the Happy Death Spiral

108. Uncritical Supercriticality

109. Evaporative Cooling of Group Beliefs

110. When None Dare Urge Restraint

111. The Robbers Cave Experiment

112. Every Cause Wants to Be a Cult

113. Guardians of the Truth

114. Guardians of the Gene Pool

115. Guardians of Ayn Rand

116. Two Cult Koans

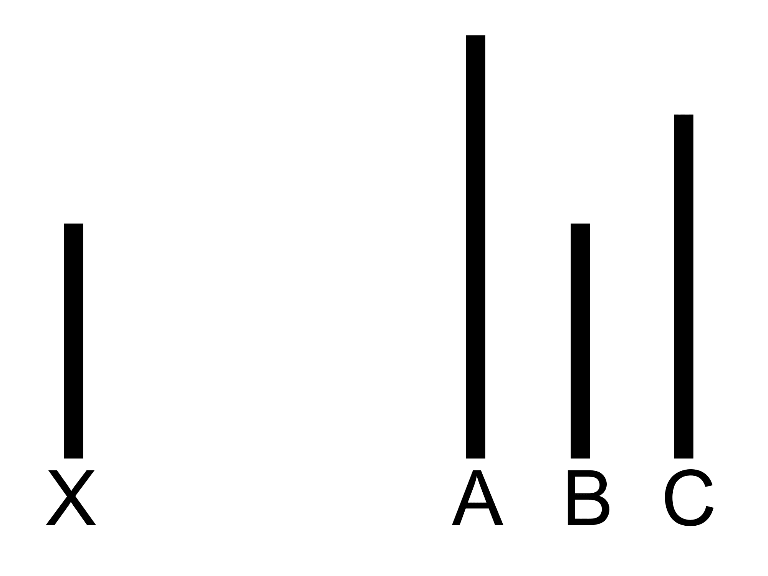

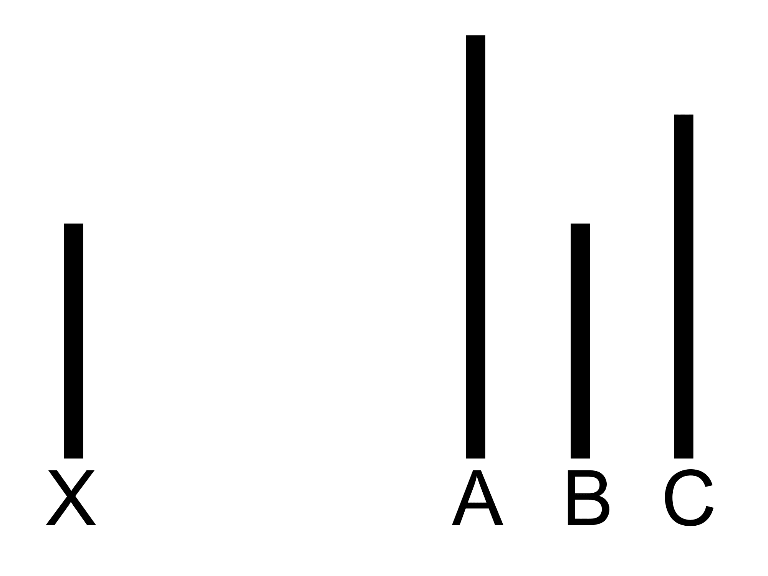

117. Asch’s Conformity Experiment

118. On Expressing Your Concerns

119. Lonely Dissent

120. Cultish Countercultishness

K. Letting Go

121. The Importance of Saying “Oops”

122. The Crackpot Offer

123. Just Lose Hope Already

124. The Proper Use of Doubt

125. You Can Face Reality

126. The Meditation on Curiosity

127. No One Can Exempt You From Rationality’s Laws

128. Leave a Line of Retreat

129. Crisis of Faith

130. The Ritual

Book III: The Machine in the Ghost

Minds: An Introduction

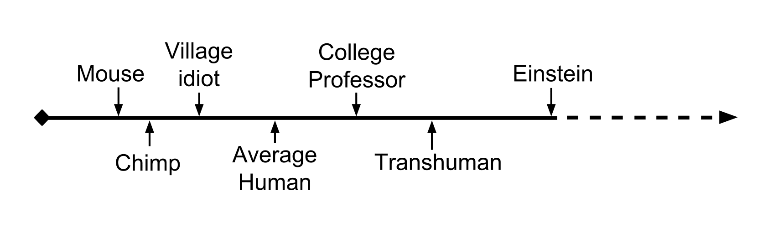

Interlude: The Power of Intelligence

L. The Simple Math of Evolution

131. An Alien God

132. The Wonder of Evolution

133. Evolutions Are Stupid (But Work Anyway)

134. No Evolutions for Corporations or Nanodevices

135. Evolving to Extinction

136. The Tragedy of Group Selectionism

137. Fake Optimization Criteria

138. Adaptation-Executers, Not Fitness-Maximizers

139. Evolutionary Psychology

140. An Especially Elegant Evolutionary Psychology Experiment

141. Superstimuli and the Collapse of Western Civilization

142. Thou Art Godshatter

M. Fragile Purposes

143. Belief in Intelligence

144. Humans in Funny Suits

145. Optimization and the Intelligence Explosion

146. Ghosts in the Machine

147. Artificial Addition

148. Terminal Values and Instrumental Values

149. Leaky Generalizations

150. The Hidden Complexity of Wishes

151. Anthropomorphic Optimism

152. Lost Purposes

N. A Human’s Guide to Words

153. The Parable of the Dagger

154. The Parable of Hemlock

155. Words as Hidden Inferences

156. Extensions and Intensions

157. Similarity Clusters

158. Typicality and Asymmetrical Similarity

159. The Cluster Structure of Thingspace

160. Disguised Queries

161. Neural Categories

162. How An Algorithm Feels From Inside

163. Disputing Definitions

164. Feel the Meaning

165. The Argument from Common Usage

166. Empty Labels

167. Taboo Your Words

168. Replace the Symbol with the Substance

169. Fallacies of Compression

170. Categorizing Has Consequences

171. Sneaking in Connotations

172. Arguing “By Definition”

173. Where to Draw the Boundary?

174. Entropy, and Short Codes

175. Mutual Information, and Density in Thingspace

176. Superexponential Conceptspace, and Simple Words

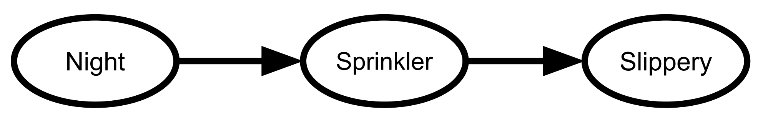

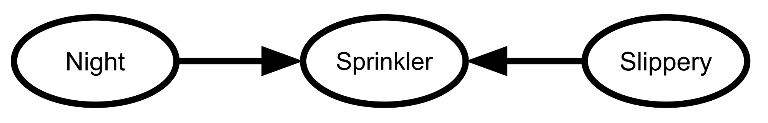

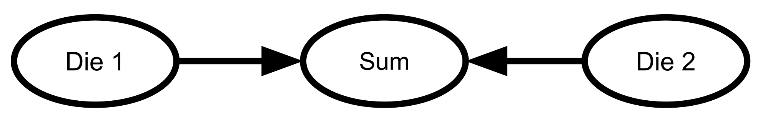

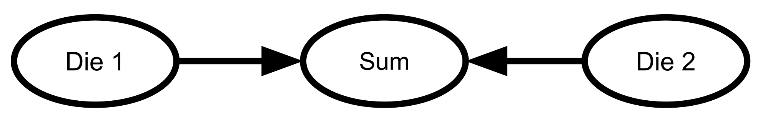

177. Conditional Independence, and Naive Bayes

178. Words as Mental Paintbrush Handles

179. Variable Question Fallacies

180. 37 Ways That Words Can Be Wrong

Interlude: An Intuitive Explanation of Bayes’s Theorem

Book IV: Mere Reality

The World: An Introduction

O. Lawful Truth

181. Universal Fire

182. Universal Law

183. Is Reality Ugly?

184. Beautiful Probability

185. Outside the Laboratory

186. The Second Law of Thermodynamics, and Engines of Cognition

187. Perpetual Motion Beliefs

188. Searching for Bayes-Structure

P. Reductionism 101

189. Dissolving the Question

190. Wrong Questions

191. Righting a Wrong Question

192. Mind Projection Fallacy

193. Probability is in the Mind

194. The Quotation is Not the Referent

195. Qualitatively Confused

196. Think Like Reality

197. Chaotic Inversion

198. Reductionism

199. Explaining vs. Explaining Away

200. Fake Reductionism

201. Savannah Poets

Q. Joy in the Merely Real

202. Joy in the Merely Real

203. Joy in Discovery

204. Bind Yourself to Reality

205. If You Demand Magic, Magic Won’t Help

206. Mundane Magic

207. The Beauty of Settled Science

208. Amazing Breakthrough Day: April 1st

209. Is Humanism a Religion Substitute?

210. Scarcity

211. The Sacred Mundane

212. To Spread Science, Keep It Secret

213. Initiation Ceremony

R. Physicalism 201

214. Hand vs. Fingers

215. Angry Atoms

216. Heat vs. Motion

217. Brain Breakthrough! It’s Made of Neurons!

218. When Anthropomorphism Became Stupid

219. A Priori

220. Reductive Reference

221. Zombies! Zombies?

222. Zombie Responses

223. The Generalized Anti-Zombie Principle

224. GAZP vs. GLUT

225. Belief in the Implied Invisible

226. Zombies: The Movie

227. Excluding the Supernatural

228. Psychic Powers

S. Quantum Physics and Many Worlds

229. Quantum Explanations

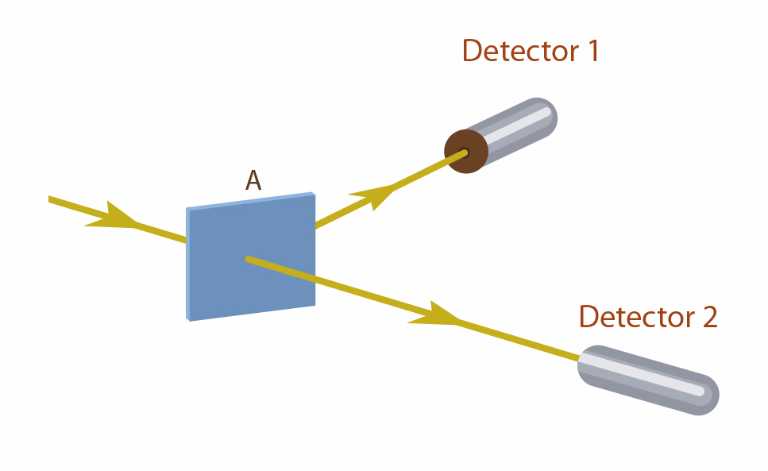

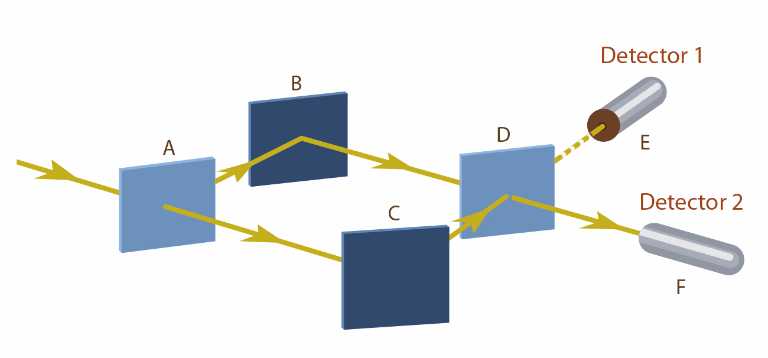

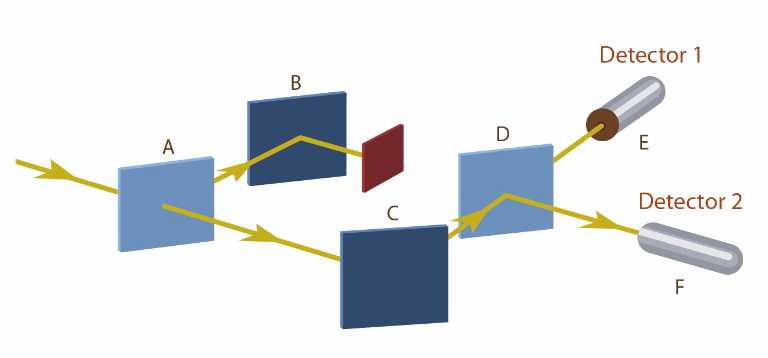

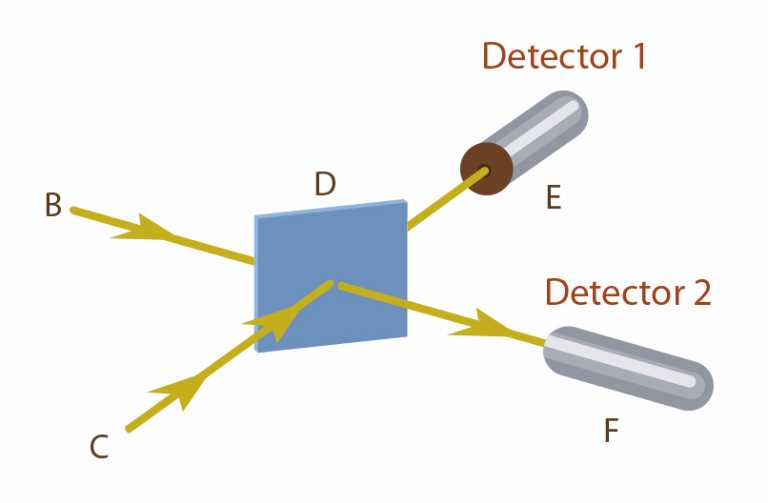

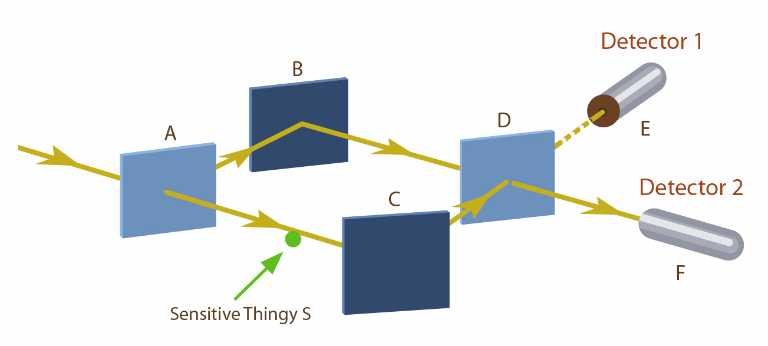

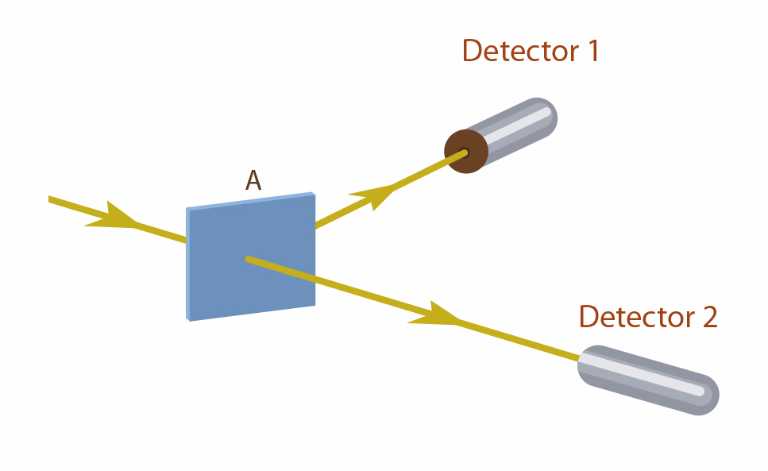

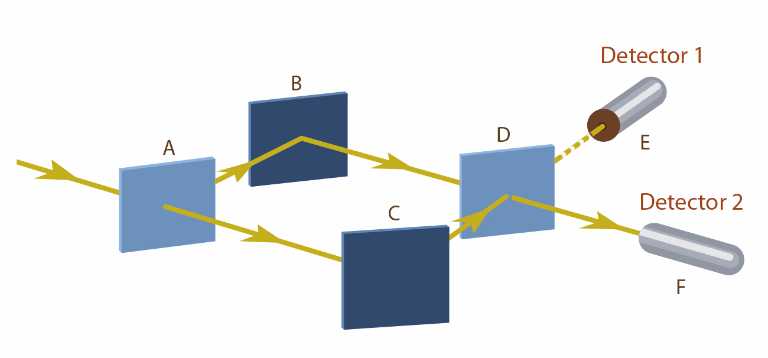

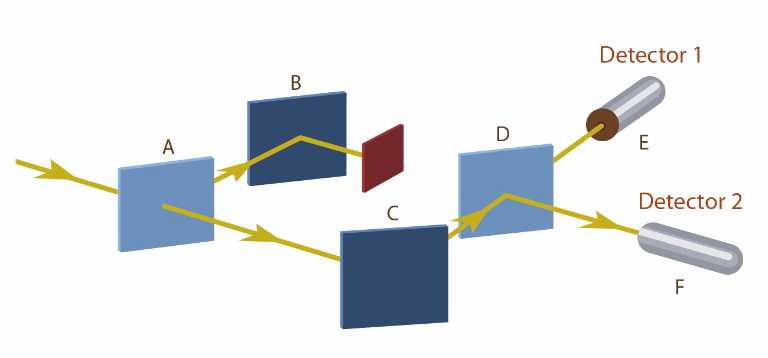

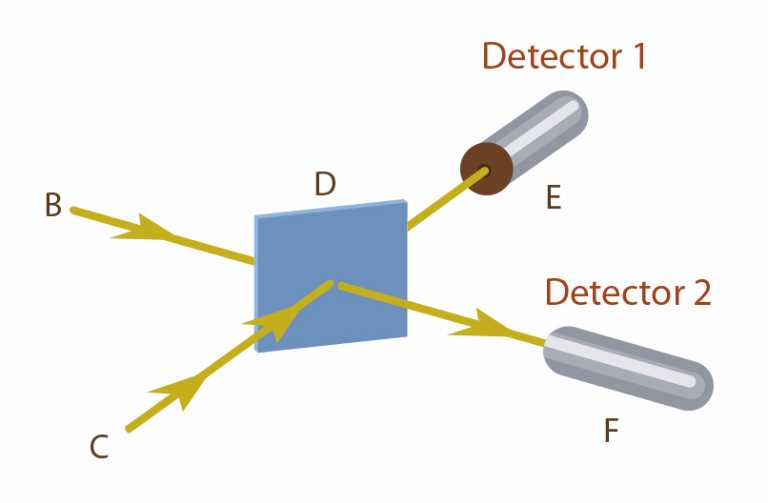

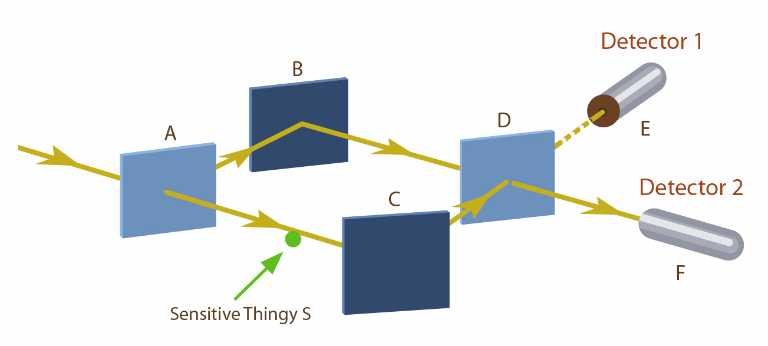

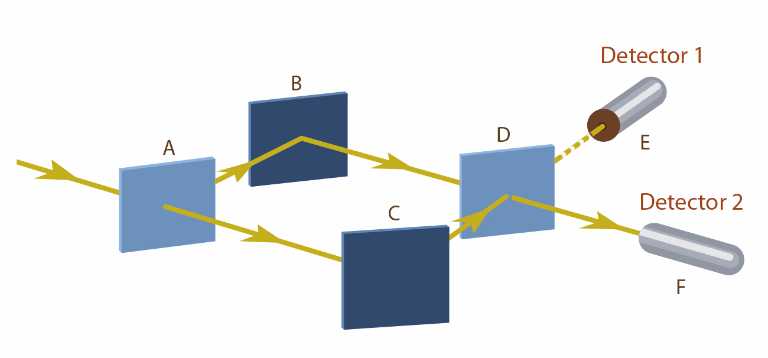

230. Configurations and Amplitude

231. Joint Configurations

232. Distinct Configurations

233. Collapse Postulates

234. Decoherence is Simple

235. Decoherence is Falsifiable and Testable

236. Privileging the Hypothesis

237. Living in Many Worlds

238. Quantum Non-Realism

239. If Many-Worlds Had Come First

240. Where Philosophy Meets Science

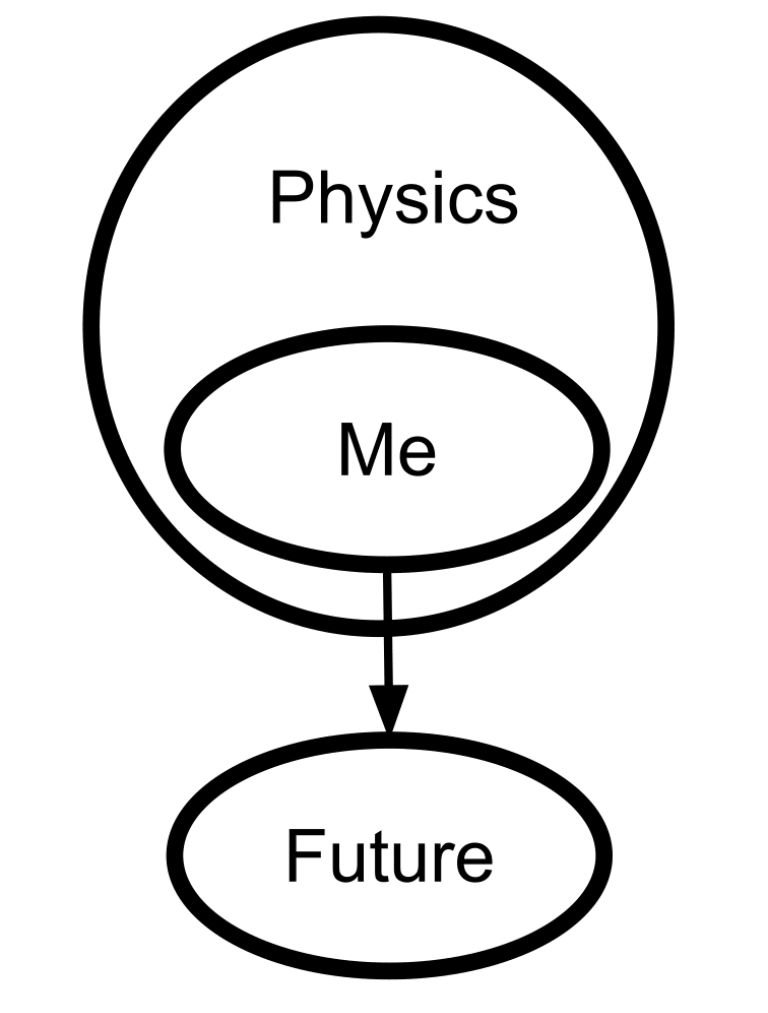

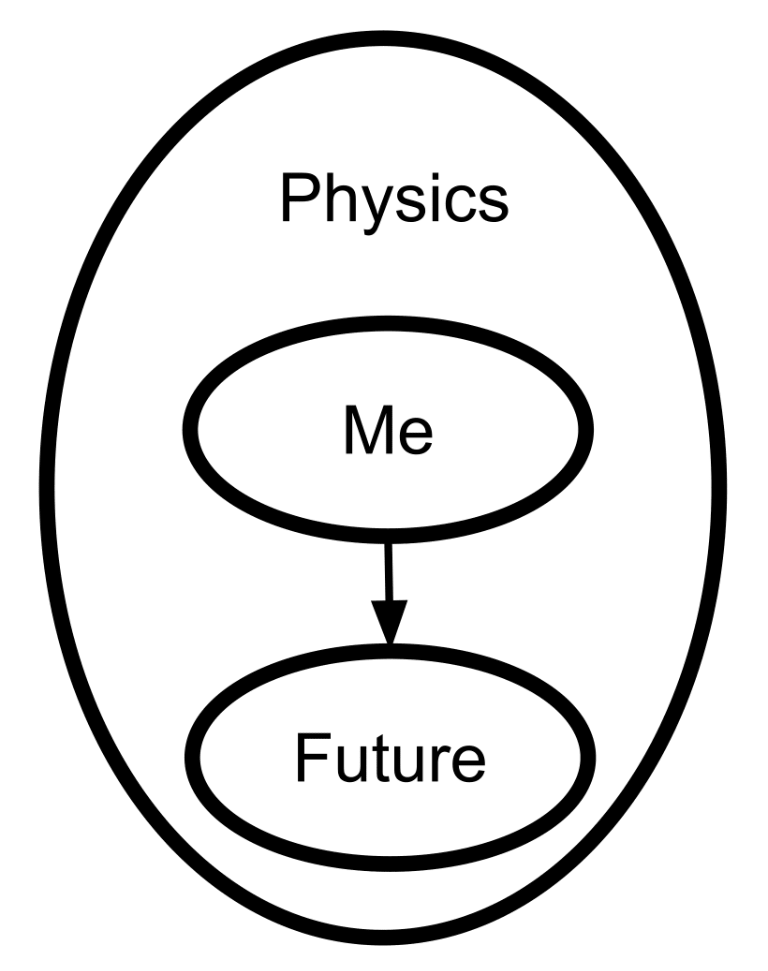

241. Thou Art Physics

242. Many Worlds, One Best Guess

T. Science and Rationality

243. The Failures of Eld Science

244. The Dilemma: Science or Bayes?

245. Science Doesn’t Trust Your Rationality

246. When Science Can’t Help

247. Science Isn’t Strict Enough

248. Do Scientists Already Know This Stuff?

249. No Safe Defense, Not Even Science

250. Changing the Definition of Science

251. Faster Than Science

252. Einstein’s Speed

253. That Alien Message

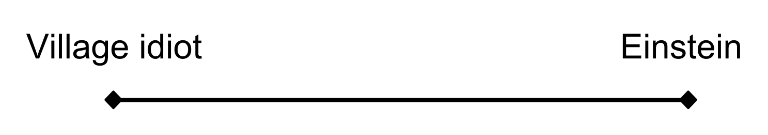

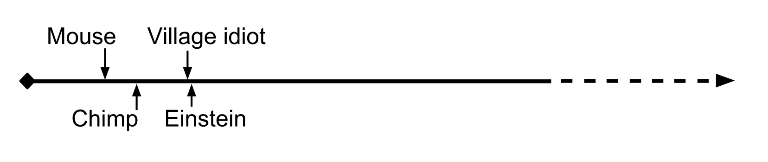

254. My Childhood Role Model

255. Einstein’s Superpowers

256. Class Project

Interlude: A Technical Explanation of Technical Explanation

Book V: Mere Goodness

Ends: An Introduction

U. Fake Preferences

257. Not for the Sake of Happiness (Alone)

258. Fake Selfishness

259. Fake Morality

260. Fake Utility Functions

261. Detached Lever Fallacy

262. Dreams of AI Design

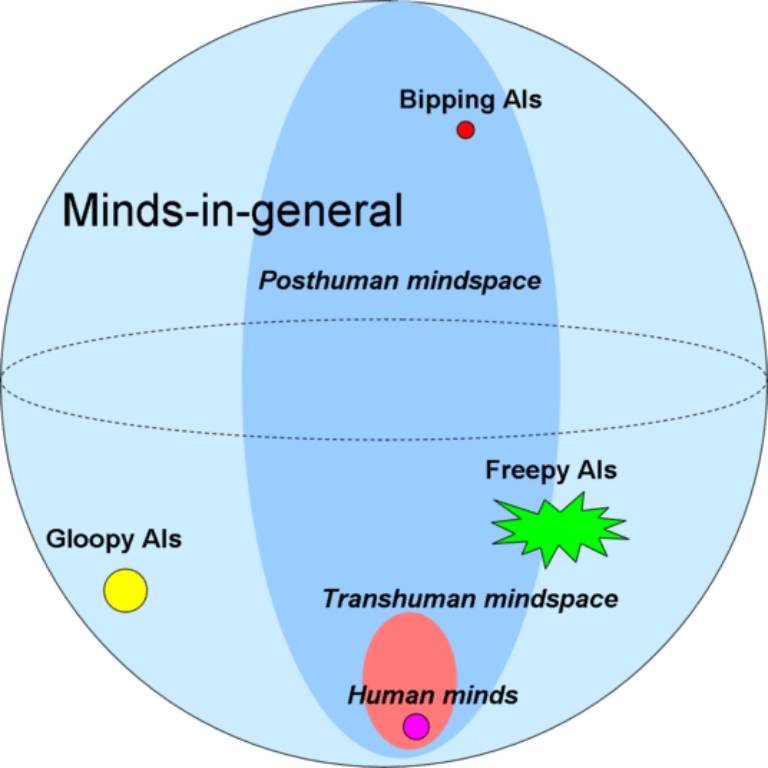

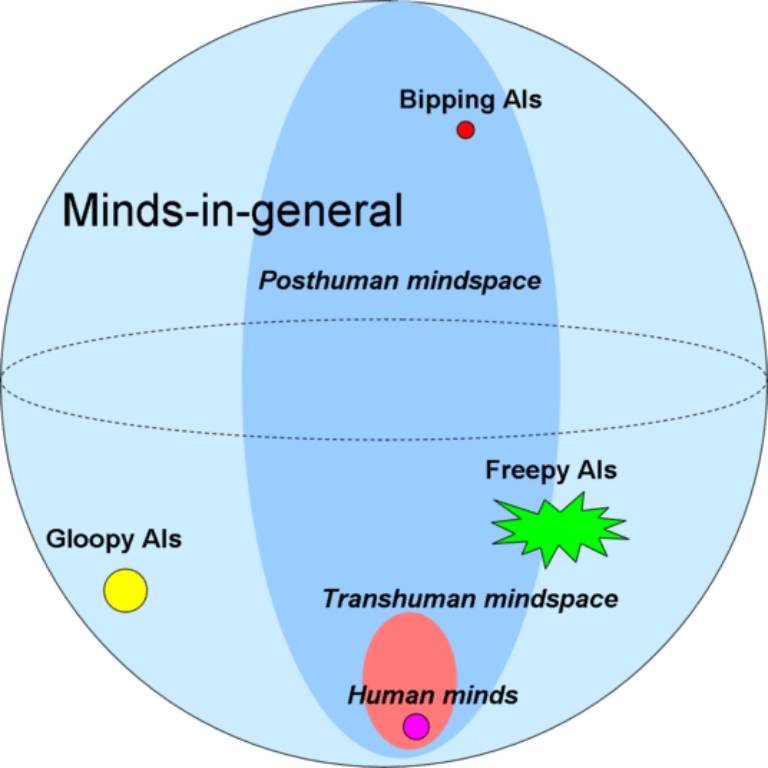

263. The Design Space of Minds-in-General

V. Value Theory

264. Where Recursive Justification Hits Bottom

265. My Kind of Reflection

266. No Universally Compelling Arguments

267. Created Already in Motion

268. Sorting Pebbles into Correct Heaps

269. 2-Place and 1-Place Words

270. What Would You Do Without Morality?

271. Changing Your Metaethics

272. Could Anything Be Right?

273. Morality as Fixed Computation

274. Magical Categories

275. The True Prisoner’s Dilemma

276. Sympathetic Minds

277. High Challenge

278. Serious Stories

279. Value is Fragile

280. The Gift We Give to Tomorrow

W. Quantified Humanism

281. Scope Insensitivity

282. One Life Against the World

283. The Allais Paradox

284. Zut Allais!

285. Feeling Moral

286. The “Intuitions” Behind “Utilitarianism”

287. Ends Don’t Justify Means (Among Humans)

288. Ethical Injunctions

289. Something to Protect

290. When (Not) to Use Probabilities

291. Newcomb’s Problem and Regret of Rationality

Interlude: The Twelve Virtues of Rationality

Book VI: Becoming Stronger

Beginnings: An Introduction

X. Yudkowsky’s Coming of Age

292. My Childhood Death Spiral

293. My Best and Worst Mistake

294. Raised in Technophilia

295. A Prodigy of Refutation

296. The Sheer Folly of Callow Youth

297. That Tiny Note of Discord

298. Fighting a Rearguard Action Against the Truth

299. My Naturalistic Awakening

300. The Level Above Mine

301. The Magnitude of His Own Folly

302. Beyond the Reach of God

303. My Bayesian Enlightenment

Y. Challenging the Difficult

304. Tsuyoku Naritai! (I Want to Become Stronger)

305. Tsuyoku vs. the Egalitarian Instinct

306. Trying to Try

307. Use the Try Harder, Luke

308. On Doing the Impossible

309. Make an Extraordinary Effort

310. Shut Up and Do the Impossible!

311. Final Words

Z. The Craft and the Community

312. Raising the Sanity Waterline

313. A Sense That More Is Possible

314. Epistemic Viciousness

315. Schools Proliferating Without Evidence

316. Three Levels of Rationality Verification

317. Why Our Kind Can’t Cooperate

318. Tolerate Tolerance

319. Your Price for Joining

320. Can Humanism Match Religion’s Output?

321. Church vs. Taskforce

322. Rationality: Common Interest of Many Causes

323. Helpless Individuals

324. Money: The Unit of Caring

325. Purchase Fuzzies and Utilons Separately

326. Bystander Apathy

327. Collective Apathy and the Internet

328. Incremental Progress and the Valley

329. Bayesians vs. Barbarians

330. Beware of Other-Optimizing

331. Practical Advice Backed by Deep Theories

332. The Sin of Underconfidence

333. Go Forth and Create the Art!

Bibliography

Preface

You hold in your hands a compilation of two years of daily blog posts. In retrospect, I look back on that project and see a large number of things I did completely wrong. I’m fine with that. Looking back and not seeing a huge number of things I did wrong would mean that neither my writing nor my understanding had improved since 2009. Oops is the sound we make when we improve our beliefs and strategies; so to look back at a time and not see anything you did wrong means that you haven’t learned anything or changed your mind since then.

It was a mistake that I didn’t write my two years of blog posts with the intention of helping people do better in their everyday lives. I wrote it with the intention of helping people solve big, difficult, important problems, and I chose impressive-sounding, abstract problems as my examples.

In retrospect, this was the second-largest mistake in my approach. It ties in to the first-largest mistake in my writing, which was that I didn’t realize that the big problem in learning this valuable way of thinking was figuring out how to practice it, not knowing the theory. I didn’t realize that part was the priority; and regarding this I can only say “Oops” and “Duh.”

Yes, sometimes those big issues really are big and really are important; but that doesn’t change the basic truth that to master skills you need to practice them and it’s harder to practice on things that are further away. (Today the Center for Applied Rationality is working on repairing this huge mistake of mine in a more systematic fashion.)

A third huge mistake I made was to focus too much on rational belief, too little on rational action.

The fourth-largest mistake I made was that I should have better organized the content I was presenting in the sequences. In particular, I should have created a wiki much earlier, and made it easier to read the posts in sequence.

That mistake at least is correctable. In the present work Rob Bensinger has reordered the posts and reorganized them as much as he can without trying to rewrite all the actual material (though he’s rewritten a bit of it).

My fifth huge mistake was that I—as I saw it—tried to speak plainly about the stupidity of what appeared to me to be stupid ideas. I did try to avoid the fallacy known as Bulverism, which is where you open your discussion by talking about how stupid people are for believing something; I would always discuss the issue first, and only afterwards say, “And so this is stupid.” But in 2009 it was an open question in my mind whether it might be important to have some people around who expressed contempt for homeopathy. I thought, and still do think, that there is an unfortunate problem wherein treating ideas courteously is processed by many people on some level as “Nothing bad will happen to me if I say I believe this; I won’t lose status if I say I believe in homeopathy,” and that derisive laughter by comedians can help people wake up from the dream.

Today I would write more courteously, I think. The discourtesy did serve a function, and I think there were people who were helped by reading it; but I now take more seriously the risk of building communities where the normal and expected reaction to low-status outsider views is open mockery and contempt.

Despite my mistake, I am happy to say that my readership has so far been amazingly good about not using my rhetoric as an excuse to bully or belittle others. (I want to single out Scott Alexander in particular here, who is a nicer person than I am and an increasingly amazing writer on these topics, and may deserve part of the credit for making the culture of Less Wrong a healthy one.)

To be able to look backwards and say that you’ve “failed” implies that you had goals. So what was it that I was trying to do?

There is a certain valuable way of thinking, which is not yet taught in schools, in this present day. This certain way of thinking is not taught systematically at all. It is just absorbed by people who grow up reading books like Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman or who have an unusually great teacher in high school.

Most famously, this certain way of thinking has to do with science, and with the experimental method. The part of science where you go out and look at the universe instead of just making things up. The part where you say “Oops” and give up on a bad theory when the experiments don’t support it.

But this certain way of thinking extends beyond that. It is deeper and more universal than a pair of goggles you put on when you enter a laboratory and take off when you leave. It applies to daily life, though this part is subtler and more difficult. But if you can’t say “Oops” and give up when it looks like something isn’t working, you have no choice but to keep shooting yourself in the foot. You have to keep reloading the shotgun and you have to keep pulling the trigger. You know people like this. And somewhere, someplace in your life you’d rather not think about, you are people like this. It would be nice if there was a certain way of thinking that could help us stop doing that.

In spite of how large my mistakes were, those two years of blog posting appeared to help a surprising number of people a surprising amount. It didn’t work reliably, but it worked sometimes.

In modern society so little is taught of the skills of rational belief and decision-making, so little of the mathematics and sciences underlying them . . . that it turns out that just reading through a massive brain-dump full of problems in philosophy and science can, yes, be surprisingly good for you. Walking through all of that, from a dozen different angles, can sometimes convey a glimpse of the central rhythm.

Because it is all, in the end, one thing. I talked about big important distant problems and neglected immediate life, but the laws governing them aren’t actually different. There are huge gaps in which parts I focused on, and I picked all the wrong examples; but it is all in the end one thing. I am proud to look back and say that, even after all the mistakes I made, and all the other times I said “Oops” . . .

Even five years later, it still appears to me that this is better than nothing.

—Eliezer Yudkowsky,

February 2015

Biases: An Introduction

by Rob Bensinger

It’s not a secret. For some reason, though, it rarely comes up in conversation, and few people are asking what we should do about it. It’s a pattern, hidden unseen behind all our triumphs and failures, unseen behind our eyes. What is it?

Imagine reaching into an urn that contains seventy white balls and thirty red ones, and plucking out ten mystery balls. Perhaps three of the ten balls will be red, and you’ll correctly guess how many red balls total were in the urn. Or perhaps you’ll happen to grab four red balls, or some other number. Then you’ll probably get the total number wrong.

This random error is the cost of incomplete knowledge, and as errors go, it’s not so bad. Your estimates won’t be incorrect on average, and the more you learn, the smaller your error will tend to be.

On the other hand, suppose that the white balls are heavier, and sink to the bottom of the urn. Then your sample may be unrepresentative in a consistent direction.

That sort of error is called “statistical bias.” When your method of learning about the world is biased, learning more may not help. Acquiring more data can even consistently worsen a biased prediction.

If you’re used to holding knowledge and inquiry in high esteem, this is a scary prospect. If we want to be sure that learning more will help us, rather than making us worse off than we were before, we need to discover and correct for biases in our data.

The idea of cognitive bias in psychology works in an analogous way. A cognitive bias is a systematic error in how we think, as opposed to a random error or one that’s merely caused by our ignorance. Whereas statistical bias skews a sample so that it less closely resembles a larger population, cognitive biases skew our beliefs so that they less accurately represent the facts, and they skew our decision-making so that it less reliably achieves our goals.

Maybe you have an optimism bias, and you find out that the red balls can be used to treat a rare tropical disease besetting your brother. You may then overestimate how many red balls the urn contains because you wish the balls were mostly red. Here, your sample isn’t what’s biased. You’re what’s biased.

Now that we’re talking about biased people, however, we have to be careful. Usually, when we call individuals or groups “biased,” we do it to chastise them for being unfair or partial. Cognitive bias is a different beast altogether. Cognitive biases are a basic part of how humans in general think, not the sort of defect we could blame on a terrible upbringing or a rotten personality.

A cognitive bias is a systematic way that your innate patterns of thought fall short of truth (or some other attainable goal, such as happiness). Like statistical biases, cognitive biases can distort our view of reality, they can’t always be fixed by just gathering more data, and their effects can add up over time. But when the miscalibrated measuring instrument you’re trying to fix is you, debiasing is a unique challenge.

Still, this is an obvious place to start. For if you can’t trust your brain, how can you trust anything else?

It would be useful to have a name for this project of overcoming cognitive bias, and of overcoming all species of error where our minds can come to undermine themselves.

We could call this project whatever we’d like. For the moment, though, I suppose “rationality” is as good a name as any.

Rational Feelings

In a Hollywood movie, being “rational” usually means that you’re a stern, hyperintellectual stoic. Think Spock from Star Trek, who “rationally” suppresses his emotions, “rationally” refuses to rely on intuitions or impulses, and is easily dumbfounded and outmaneuvered upon encountering an erratic or “irrational” opponent.

There’s a completely different notion of “rationality” studied by mathematicians, psychologists, and social scientists. Roughly, it’s the idea of doing the best you can with what you’ve got. A rational person, no matter how out of their depth they are, forms the best beliefs they can with the evidence they’ve got. A rational person, no matter how terrible a situation they’re stuck in, makes the best choices they can to improve their odds of success.

Real-world rationality isn’t about ignoring your emotions and intuitions. For a human, rationality often means becoming more self-aware about your feelings, so you can factor them into your decisions.

Rationality can even be about knowing when not to overthink things. When selecting a poster to put on their wall, or predicting the outcome of a basketball game, experimental subjects have been found to perform worse if they carefully analyzed their reasons., There are some problems where conscious deliberation serves us better, and others where snap judgments serve us better.

Psychologists who work on dual process theories distinguish the brain’s “System 1” processes (fast, implicit, associative, automatic cognition) from its “System 2” processes (slow, explicit, intellectual, controlled cognition). The stereotype is for rationalists to rely entirely on System 2, disregarding their feelings and impulses. Looking past the stereotype, someone who is actually being rational—actually achieving their goals, actually mitigating the harm from their cognitive biases—would rely heavily on System-1 habits and intuitions where they’re reliable.

Unfortunately, System 1 on its own seems to be a terrible guide to “when should I trust System 1?” Our untrained intuitions don’t tell us when we ought to stop relying on them. Being biased and being unbiased feel the same.

On the other hand, as behavioral economist Dan Ariely notes: we’re predictably irrational. We screw up in the same ways, again and again, systematically.

If we can’t use our gut to figure out when we’re succumbing to a cognitive bias, we may still be able to use the sciences of mind.

The Many Faces of Bias

To solve problems, our brains have evolved to employ cognitive heuristics—rough shortcuts that get the right answer often, but not all the time. Cognitive biases arise when the corners cut by these heuristics result in a relatively consistent and discrete mistake.

The representativeness heuristic, for example, is our tendency to assess phenomena by how representative they seem of various categories. This can lead to biases like the conjunction fallacy. Tversky and Kahneman found that experimental subjects considered it less likely that a strong tennis player would “lose the first set” than that he would “lose the first set but win the match.” Making a comeback seems more typical of a strong player, so we overestimate the probability of this complicated-but-sensible-sounding narrative compared to the probability of a strictly simpler scenario.

The representativeness heuristic can also contribute to base rate neglect, where we ground our judgments in how intuitively “normal” a combination of attributes is, neglecting how common each attribute is in the population at large. Is it more likely that Steve is a shy librarian, or that he’s a shy salesperson? Most people answer this kind of question by thinking about whether “shy” matches their stereotypes of those professions. They fail to take into consideration how much more common salespeople are than librarians—seventy-five times as common, in the United States.

Other examples of biases include duration neglect (evaluating experiences without regard to how long they lasted), the sunk cost fallacy (feeling committed to things you’ve spent resources on in the past, when you should be cutting your losses and moving on), and confirmation bias (giving more weight to evidence that confirms what we already believe).,

Knowing about a bias, however, is rarely enough to protect you from it. In a study of bias blindness, experimental subjects predicted that if they learned a painting was the work of a famous artist, they’d have a harder time neutrally assessing the quality of the painting. And, indeed, subjects who were told a painting’s author and were asked to evaluate its quality exhibited the very bias they had predicted, relative to a control group. When asked afterward, however, the very same subjects claimed that their assessments of the paintings had been objective and unaffected by the bias—in all groups!,

We’re especially loathe to think of our views as inaccurate compared to the views of others. Even when we correctly identify others’ biases, we have a special bias blind spot when it comes to our own flaws. We fail to detect any “biased-feeling thoughts” when we introspect, and so draw the conclusion that we must just be more objective than everyone else.

Studying biases can in fact make you more vulnerable to overconfidence and confirmation bias, as you come to see the influence of cognitive biases all around you—in everyone but yourself. And the bias blind spot, unlike many biases, is especially severe among people who are especially intelligent, thoughtful, and open-minded.,

This is cause for concern.

Still . . . it does seem like we should be able to do better. It’s known that we can reduce base rate neglect by thinking of probabilities as frequencies of objects or events. We can minimize duration neglect by directing more attention to duration and depicting it graphically. People vary in how strongly they exhibit different biases, so there should be a host of yet-unknown ways to influence how biased we are.

If we want to improve, however, it’s not enough for us to pore over lists of cognitive biases. The approach to debiasing in Rationality: From AI to Zombies is to communicate a systematic understanding of why good reasoning works, and of how the brain falls short of it. To the extent this volume does its job, its approach can be compared to the one described in Serfas, who notes that “years of financially related work experience” didn’t affect people’s susceptibility to the sunk cost bias, whereas “the number of accounting courses attended” did help.

As a consequence, it might be necessary to distinguish between experience and expertise, with expertise meaning “the development of a schematic principle that involves conceptual understanding of the problem,” which in turn enables the decision maker to recognize particular biases. However, using expertise as countermeasure requires more than just being familiar with the situational content or being an expert in a particular domain. It requires that one fully understand the underlying rationale of the respective bias, is able to spot it in the particular setting, and also has the appropriate tools at hand to counteract the bias.

The goal of this book is to lay the groundwork for creating rationality “expertise.” That means acquiring a deep understanding of the structure of a very general problem: human bias, self-deception, and the thousand paths by which sophisticated thought can defeat itself.

A Word About This Text

Rationality: From AI to Zombies began its life as a series of essays by Eliezer Yudkowsky, published between 2006 and 2009 on the economics blog Overcoming Bias and its spin-off community blog Less Wrong. I’ve worked with Yudkowsky for the last year at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI), a nonprofit he founded in 2000 to study the theoretical requirements for smarter-than-human artificial intelligence (AI).

Reading his blog posts got me interested in his work. He impressed me with his ability to concisely communicate insights it had taken me years of studying analytic philosophy to internalize. In seeking to reconcile science’s anarchic and skeptical spirit with a rigorous and systematic approach to inquiry, Yudkowsky tries not just to refute but to understand the many false steps and blind alleys bad philosophy (and bad lack-of-philosophy) can produce. My hope in helping organize these essays into a book is to make it easier to dive in to them, and easier to appreciate them as a coherent whole.

The resultant rationality primer is frequently personal and irreverent—drawing, for example, from Yudkowsky’s experiences with his Orthodox Jewish mother (a psychiatrist) and father (a physicist), and from conversations on chat rooms and mailing lists. Readers who are familiar with Yudkowsky from Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, his science-oriented take-off of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, will recognize the same irreverent iconoclasm, and many of the same core concepts.

Stylistically, the essays in this book run the gamut from “lively textbook” to “compendium of thoughtful vignettes” to “riotous manifesto,” and the content is correspondingly varied. Rationality: From AI to Zombies collects hundreds of Yudkowsky’s blog posts into twenty-six “sequences,” chapter-like series of thematically linked posts. The sequences in turn are grouped into six books, covering the following topics:

Book 1—Map and Territory. What is a belief, and what makes some beliefs work better than others? These four sequences explain the Bayesian notions of rationality, belief, and evidence. A running theme: the things we call “explanations” or “theories” may not always function like maps for navigating the world. As a result, we risk mixing up our mental maps with the other objects in our toolbox.

Book 2—How to Actually Change Your Mind. This truth thing seems pretty handy. Why, then, do we keep jumping to conclusions, digging our heels in, and recapitulating the same mistakes? Why are we so bad at acquiring accurate beliefs, and how can we do better? These seven sequences discuss motivated reasoning and confirmation bias, with a special focus on hard-to-spot species of self-deception and the trap of “using arguments as soldiers.”

Book 3—The Machine in the Ghost. Why haven’t we evolved to be more rational? Even taking into account resource constraints, it seems like we could be getting a lot more epistemic bang for our evidential buck. To get a realistic picture of how and why our minds execute their biological functions, we need to crack open the hood and see how evolution works, and how our brains work, with more precision. These three sequences illustrate how even philosophers and scientists can be led astray when they rely on intuitive, non-technical evolutionary or psychological accounts. By locating our minds within a larger space of goal-directed systems, we can identify some of the peculiarities of human reasoning and appreciate how such systems can “lose their purpose.”

Book 4—Mere Reality. What kind of world do we live in? What is our place in that world? Building on the previous sequences’ examples of how evolutionary and cognitive models work, these six sequences explore the nature of mind and the character of physical law. In addition to applying and generalizing past lessons on scientific mysteries and parsimony, these essays raise new questions about the role science should play in individual rationality.

Book 5—Mere Goodness. What makes something valuable—morally, or aesthetically, or prudentially? These three sequences ask how we can justify, revise, and naturalize our values and desires. The aim will be to find a way to understand our goals without compromising our efforts to actually achieve them. Here the biggest challenge is knowing when to trust your messy, complicated case-by-case impulses about what’s right and wrong, and when to replace them with simple exceptionless principles.

Book 6—Becoming Stronger. How can individuals and communities put all this into practice? These three sequences begin with an autobiographical account of Yudkowsky’s own biggest philosophical blunders, with advice on how he thinks others might do better. The book closes with recommendations for developing evidence-based applied rationality curricula, and for forming groups and institutions to support interested students, educators, researchers, and friends.

The sequences are also supplemented with “interludes,” essays taken from Yudkowsky’s personal website, http://www.yudkowsky.net. These tie in to the sequences in various ways; e.g., The Twelve Virtues of Rationality poetically summarizes many of the lessons of Rationality: From AI to Zombies, and is often quoted in other essays.

Clicking the asterisk at the bottom of an essay will take you to the original version of it on Less Wrong (where you can leave comments) or on Yudkowsky’s website. You can also find a glossary for Rationality: From AI to Zombies terminology online, at http://wiki.lesswrong.com/wiki/RAZ_Glossary.

Map and Territory

This, the first book, begins with a sequence on cognitive bias: “Predictably Wrong.” The rest of the book won’t stick to just this topic; bad habits and bad ideas matter, even when they arise from our minds’ contents as opposed to our minds’ structure. Thus evolved and invented errors will both be on display in subsequent sequences, beginning with a discussion in “Fake Beliefs” of ways that one’s expectations can come apart from one’s professed beliefs.

An account of irrationality would also be incomplete if it provided no theory about how rationality works—or if its “theory” only consisted of vague truisms, with no precise explanatory mechanism. The “Noticing Confusion” sequence asks why it’s useful to base one’s behavior on “rational” expectations, and what it feels like to do so.

“Mysterious Answers” next asks whether science resolves these problems for us. Scientists base their models on repeatable experiments, not speculation or hearsay. And science has an excellent track record compared to anecdote, religion, and . . . pretty much everything else. Do we still need to worry about “fake” beliefs, confirmation bias, hindsight bias, and the like when we’re working with a community of people who want to explain phenomena, not just tell appealing stories?

This is then followed by The Simple Truth, a stand-alone allegory on the nature of knowledge and belief.

It is cognitive bias, however, that provides the clearest and most direct glimpse into the stuff of our psychology, into the shape of our heuristics and the logic of our limitations. It is with bias that we will begin.

There is a passage in the Zhuangzi, a proto-Daoist philosophical text, that says: “The fish trap exists because of the fish; once you’ve gotten the fish, you can forget the trap.”

I invite you to explore this book in that spirit. Use it like you’d use a fish trap, ever mindful of the purpose you have for it. Carry with you what you can use, so long as it continues to have use; discard the rest. And may your purpose serve you well.

Acknowledgments

I am stupendously grateful to Nate Soares, Elizabeth Tarleton, Paul Crowley, Brienne Strohl, Adam Freese, Helen Toner, and dozens of volunteers for proofreading portions of this book.

Special and sincere thanks to Alex Vermeer, who steered this book to completion, and Tsvi Benson-Tilsen, who combed through the entire book to ensure its readability and consistency.

*

Book I

Map and Territory

Part A

Predictably Wrong

1

What Do I Mean By “Rationality”?

I mean:

- Epistemic rationality: systematically improving the accuracy of your beliefs.

- Instrumental rationality: systematically achieving your values.

When you open your eyes and look at the room around you, you’ll locate your laptop in relation to the table, and you’ll locate a bookcase in relation to the wall. If something goes wrong with your eyes, or your brain, then your mental model might say there’s a bookcase where no bookcase exists, and when you go over to get a book, you’ll be disappointed.

This is what it’s like to have a false belief, a map of the world that doesn’t correspond to the territory. Epistemic rationality is about building accurate maps instead. This correspondence between belief and reality is commonly called “truth,” and I’m happy to call it that.

Instrumental rationality, on the other hand, is about steering reality—sending the future where you want it to go. It’s the art of choosing actions that lead to outcomes ranked higher in your preferences. I sometimes call this “winning.”

So rationality is about forming true beliefs and making winning decisions.

Pursuing “truth” here doesn’t mean dismissing uncertain or indirect evidence. Looking at the room around you and building a mental map of it isn’t different, in principle, from believing that the Earth has a molten core, or that Julius Caesar was bald. Those questions, being distant from you in space and time, might seem more airy and abstract than questions about your bookcase. Yet there are facts of the matter about the state of the Earth’s core in 2015 CE and about the state of Caesar’s head in 50 BCE. These facts may have real effects upon you even if you never find a way to meet Caesar or the core face-to-face.

And “winning” here need not come at the expense of others. The project of life can be about collaboration or self-sacrifice, rather than about competition. “Your values” here means anything you care about, including other people. It isn’t restricted to selfish values or unshared values.

When people say “X is rational!” it’s usually just a more strident way of saying “I think X is true” or “I think X is good.” So why have an additional word for “rational” as well as “true” and “good”?

An analogous argument can be given against using “true.” There is no need to say “it is true that snow is white” when you could just say “snow is white.” What makes the idea of truth useful is that it allows us to talk about the general features of map-territory correspondence. “True models usually produce better experimental predictions than false models” is a useful generalization, and it’s not one you can make without using a concept like “true” or “accurate.”

Similarly, “Rational agents make decisions that maximize the probabilistic expectation of a coherent utility function” is the kind of thought that depends on a concept of (instrumental) rationality, whereas “It’s rational to eat vegetables” can probably be replaced with “It’s useful to eat vegetables” or “It’s in your interest to eat vegetables.” We need a concept like “rational” in order to note general facts about those ways of thinking that systematically produce truth or value—and the systematic ways in which we fall short of those standards.

Sometimes experimental psychologists uncover human reasoning that seems very strange. For example, someone rates the probability “Bill plays jazz” as less than the probability “Bill is an accountant who plays jazz.” This seems like an odd judgment, since any particular jazz-playing accountant is obviously a jazz player. But to what higher vantage point do we appeal in saying that the judgment is wrong?

Experimental psychologists use two gold standards: probability theory, and decision theory.

Probability theory is the set of laws underlying rational belief. The mathematics of probability describes equally and without distinction (a) figuring out where your bookcase is, (b) figuring out the temperature of the Earth’s core, and (c) estimating how many hairs were on Julius Caesar’s head. It’s all the same problem of how to process the evidence and observations to revise (“update”) one’s beliefs. Similarly, decision theory is the set of laws underlying rational action, and is equally applicable regardless of what one’s goals and available options are.

Let “P(such-and-such)” stand for “the probability that such-and-such happens,” and P(A,B) for “the probability that both A and B happen.” Since it is a universal law of probability theory that P(A) ≥ P(A,B), the judgment that P(Bill plays jazz) is less than P(Bill plays jazz, Bill is an accountant) is labeled incorrect.

To keep it technical, you would say that this probability judgment is non-Bayesian. Beliefs and actions that are rational in this mathematically well-defined sense are called “Bayesian.”

Note that the modern concept of rationality is not about reasoning in words. I gave the example of opening your eyes, looking around you, and building a mental model of a room containing a bookcase against the wall. The modern concept of rationality is general enough to include your eyes and your brain’s visual areas as things-that-map. It includes your wordless intuitions as well. The math doesn’t care whether we use the same English-language word, “rational,” to refer to Spock and to refer to Bayesianism. The math models good ways of achieving goals or mapping the world, regardless of whether those ways fit our preconceptions and stereotypes about what “rationality” is supposed to be.

This does not quite exhaust the problem of what is meant in practice by “rationality,” for two major reasons:

First, the Bayesian formalisms in their full form are computationally intractable on most real-world problems. No one can actually calculate and obey the math, any more than you can predict the stock market by calculating the movements of quarks.

This is why there is a whole site called “Less Wrong,” rather than a single page that simply states the formal axioms and calls it a day. There’s a whole further art to finding the truth and accomplishing value from inside a human mind: we have to learn our own flaws, overcome our biases, prevent ourselves from self-deceiving, get ourselves into good emotional shape to confront the truth and do what needs doing, et cetera, et cetera.

Second, sometimes the meaning of the math itself is called into question. The exact rules of probability theory are called into question by, e.g., anthropic problems in which the number of observers is uncertain. The exact rules of decision theory are called into question by, e.g., Newcomblike problems in which other agents may predict your decision before it happens.

In cases like these, it is futile to try to settle the problem by coming up with some new definition of the word “rational” and saying, “Therefore my preferred answer, by definition, is what is meant by the word ‘rational.’” This simply raises the question of why anyone should pay attention to your definition. I’m not interested in probability theory because it is the holy word handed down from Laplace. I’m interested in Bayesian-style belief-updating (with Occam priors) because I expect that this style of thinking gets us systematically closer to, you know, accuracy, the map that reflects the territory.

And then there are questions of how to think that seem not quite answered by either probability theory or decision theory—like the question of how to feel about the truth once you have it. Here, again, trying to define “rationality” a particular way doesn’t support an answer, but merely presumes one.

I am not here to argue the meaning of a word, not even if that word is “rationality.” The point of attaching sequences of letters to particular concepts is to let two people communicate—to help transport thoughts from one mind to another. You cannot change reality, or prove the thought, by manipulating which meanings go with which words.

So if you understand what concept I am generally getting at with this word “rationality,” and with the sub-terms “epistemic rationality” and “instrumental rationality,” we have communicated: we have accomplished everything there is to accomplish by talking about how to define “rationality.” What’s left to discuss is not what meaning to attach to the syllables “ra-tio-na-li-ty”; what’s left to discuss is what is a good way to think.

If you say, “It’s (epistemically) rational for me to believe X, but the truth is Y,” then you are probably using the word “rational” to mean something other than what I have in mind. (E.g., “rationality” should be consistent under reflection—“rationally” looking at the evidence, and “rationally” considering how your mind processes the evidence, shouldn’t lead to two different conclusions.)

Similarly, if you find yourself saying, “The (instrumentally) rational thing for me to do is X, but the right thing for me to do is Y,” then you are almost certainly using some other meaning for the word “rational” or the word “right.” I use the term “rationality” normatively, to pick out desirable patterns of thought.

In this case—or in any other case where people disagree about word meanings—you should substitute more specific language in place of “rational”: “The self-benefiting thing to do is to run away, but I hope I would at least try to drag the child off the railroad tracks,” or “Causal decision theory as usually formulated says you should two-box on Newcomb’s Problem, but I’d rather have a million dollars.”

In fact, I recommend reading back through this essay, replacing every instance of “rational” with “foozal,” and seeing if that changes the connotations of what I’m saying any. If so, I say: strive not for rationality, but for foozality.

The word “rational” has potential pitfalls, but there are plenty of non-borderline cases where “rational” works fine to communicate what I’m getting at. Likewise “irrational.” In these cases I’m not afraid to use it.

Yet one should be careful not to overuse that word. One receives no points merely for pronouncing it loudly. If you speak overmuch of the Way, you will not attain it.

2

Feeling Rational

A popular belief about “rationality” is that rationality opposes all emotion—that all our sadness and all our joy are automatically anti-logical by virtue of being feelings. Yet strangely enough, I can’t find any theorem of probability theory which proves that I should appear ice-cold and expressionless.

So is rationality orthogonal to feeling? No; our emotions arise from our models of reality. If I believe that my dead brother has been discovered alive, I will be happy; if I wake up and realize it was a dream, I will be sad. P. C. Hodgell said: “That which can be destroyed by the truth should be.” My dreaming self’s happiness was opposed by truth. My sadness on waking is rational; there is no truth which destroys it.

Rationality begins by asking how-the-world-is, but spreads virally to any other thought which depends on how we think the world is. Your beliefs about “how-the-world-is” can concern anything you think is out there in reality, anything that either does or does not exist, any member of the class “things that can make other things happen.” If you believe that there is a goblin in your closet that ties your shoes’ laces together, then this is a belief about how-the-world-is. Your shoes are real—you can pick them up. If there’s something out there that can reach out and tie your shoelaces together, it must be real too, part of the vast web of causes and effects we call the “universe.”

Feeling angry at the goblin who tied your shoelaces involves a state of mind that is not just about how-the-world-is. Suppose that, as a Buddhist or a lobotomy patient or just a very phlegmatic person, finding your shoelaces tied together didn’t make you angry. This wouldn’t affect what you expected to see in the world—you’d still expect to open up your closet and find your shoelaces tied together. Your anger or calm shouldn’t affect your best guess here, because what happens in your closet does not depend on your emotional state of mind; though it may take some effort to think that clearly.

But the angry feeling is tangled up with a state of mind that is about how-the-world-is; you become angry because you think the goblin tied your shoelaces. The criterion of rationality spreads virally, from the initial question of whether or not a goblin tied your shoelaces, to the resulting anger.

Becoming more rational—arriving at better estimates of how-the-world-is—can diminish feelings or intensify them. Sometimes we run away from strong feelings by denying the facts, by flinching away from the view of the world that gave rise to the powerful emotion. If so, then as you study the skills of rationality and train yourself not to deny facts, your feelings will become stronger.

In my early days I was never quite certain whether it was all right to feel things strongly—whether it was allowed, whether it was proper. I do not think this confusion arose only from my youthful misunderstanding of rationality. I have observed similar troubles in people who do not even aspire to be rationalists; when they are happy, they wonder if they are really allowed to be happy, and when they are sad, they are never quite sure whether to run away from the emotion or not. Since the days of Socrates at least, and probably long before, the way to appear cultured and sophisticated has been to never let anyone see you care strongly about anything. It’s embarrassing to feel—it’s just not done in polite society. You should see the strange looks I get when people realize how much I care about rationality. It’s not the unusual subject, I think, but that they’re not used to seeing sane adults who visibly care about anything.

But I know, now, that there’s nothing wrong with feeling strongly. Ever since I adopted the rule of “That which can be destroyed by the truth should be,” I’ve also come to realize “That which the truth nourishes should thrive.” When something good happens, I am happy, and there is no confusion in my mind about whether it is rational for me to be happy. When something terrible happens, I do not flee my sadness by searching for fake consolations and false silver linings. I visualize the past and future of humankind, the tens of billions of deaths over our history, the misery and fear, the search for answers, the trembling hands reaching upward out of so much blood, what we could become someday when we make the stars our cities, all that darkness and all that light—I know that I can never truly understand it, and I haven’t the words to say. Despite all my philosophy I am still embarrassed to confess strong emotions, and you’re probably uncomfortable hearing them. But I know, now, that it is rational to feel.

3

Why Truth? And . . .

Some of the comments on Overcoming Bias have touched on the question of why we ought to seek truth. (Thankfully not many have questioned what truth is.) Our shaping motivation for configuring our thoughts to rationality, which determines whether a given configuration is “good” or “bad,” comes from whyever we wanted to find truth in the first place.

It is written: “The first virtue is curiosity.” Curiosity is one reason to seek truth, and it may not be the only one, but it has a special and admirable purity. If your motive is curiosity, you will assign priority to questions according to how the questions, themselves, tickle your personal aesthetic sense. A trickier challenge, with a greater probability of failure, may be worth more effort than a simpler one, just because it is more fun.

As I noted, people often think of rationality and emotion as adversaries. Since curiosity is an emotion, I suspect that some people will object to treating curiosity as a part of rationality. For my part, I label an emotion as “not rational” if it rests on mistaken beliefs, or rather, on mistake-producing epistemic conduct: “If the iron approaches your face, and you believe it is hot, and it is cool, the Way opposes your fear. If the iron approaches your face, and you believe it is cool, and it is hot, the Way opposes your calm.” Conversely, then, an emotion that is evoked by correct beliefs or epistemically rational thinking is a “rational emotion”; and this has the advantage of letting us regard calm as an emotional state, rather than a privileged default.

When people think of “emotion” and “rationality” as opposed, I suspect that they are really thinking of System 1 and System 2—fast perceptual judgments versus slow deliberative judgments. Deliberative judgments aren’t always true, and perceptual judgments aren’t always false; so it is very important to distinguish that dichotomy from “rationality.” Both systems can serve the goal of truth, or defeat it, depending on how they are used.

Besides sheer emotional curiosity, what other motives are there for desiring truth? Well, you might want to accomplish some specific real-world goal, like building an airplane, and therefore you need to know some specific truth about aerodynamics. Or more mundanely, you want chocolate milk, and therefore you want to know whether the local grocery has chocolate milk, so you can choose whether to walk there or somewhere else. If this is the reason you want truth, then the priority you assign to your questions will reflect the expected utility of their information—how much the possible answers influence your choices, how much your choices matter, and how much you expect to find an answer that changes your choice from its default.

To seek truth merely for its instrumental value may seem impure—should we not desire the truth for its own sake?—but such investigations are extremely important because they create an outside criterion of verification: if your airplane drops out of the sky, or if you get to the store and find no chocolate milk, it’s a hint that you did something wrong. You get back feedback on which modes of thinking work, and which don’t. Pure curiosity is a wonderful thing, but it may not linger too long on verifying its answers, once the attractive mystery is gone. Curiosity, as a human emotion, has been around since long before the ancient Greeks. But what set humanity firmly on the path of Science was noticing that certain modes of thinking uncovered beliefs that let us manipulate the world. As far as sheer curiosity goes, spinning campfire tales of gods and heroes satisfied that desire just as well, and no one realized that anything was wrong with that.

Are there motives for seeking truth besides curiosity and pragmatism? The third reason that I can think of is morality: You believe that to seek the truth is noble and important and worthwhile. Though such an ideal also attaches an intrinsic value to truth, it’s a very different state of mind from curiosity. Being curious about what’s behind the curtain doesn’t feel the same as believing that you have a moral duty to look there. In the latter state of mind, you are a lot more likely to believe that someone else should look behind the curtain, too, or castigate them if they deliberately close their eyes. For this reason, I would also label as “morality” the belief that truthseeking is pragmatically important to society, and therefore is incumbent as a duty upon all. Your priorities, under this motivation, will be determined by your ideals about which truths are most important (not most useful or most intriguing), or about when, under what circumstances, the duty to seek truth is at its strongest.

I tend to be suspicious of morality as a motivation for rationality, not because I reject the moral ideal, but because it invites certain kinds of trouble. It is too easy to acquire, as learned moral duties, modes of thinking that are dreadful missteps in the dance. Consider Mr. Spock of Star Trek, a naive archetype of rationality. Spock’s emotional state is always set to “calm,” even when wildly inappropriate. He often gives many significant digits for probabilities that are grossly uncalibrated. (E.g., “Captain, if you steer the Enterprise directly into that black hole, our probability of surviving is only 2.234%.” Yet nine times out of ten the Enterprise is not destroyed. What kind of tragic fool gives four significant digits for a figure that is off by two orders of magnitude?) Yet this popular image is how many people conceive of the duty to be “rational”—small wonder that they do not embrace it wholeheartedly. To make rationality into a moral duty is to give it all the dreadful degrees of freedom of an arbitrary tribal custom. People arrive at the wrong answer, and then indignantly protest that they acted with propriety, rather than learning from their mistake.

And yet if we’re going to improve our skills of rationality, go beyond the standards of performance set by hunter-gatherers, we’ll need deliberate beliefs about how to think with propriety. When we write new mental programs for ourselves, they start out in System 2, the deliberate system, and are only slowly—if ever—trained into the neural circuitry that underlies System 1. So if there are certain kinds of thinking that we find we want to avoid—like, say, biases—it will end up represented, within System 2, as an injunction not to think that way; a professed duty of avoidance.

If we want the truth, we can most effectively obtain it by thinking in certain ways, rather than others; these are the techniques of rationality. And some of the techniques of rationality involve overcoming a certain class of obstacles, the biases . . .

4

. . . What’s a Bias, Again?

A bias is a certain kind of obstacle to our goal of obtaining truth. (Its character as an “obstacle” stems from this goal of truth.) However, there are many obstacles that are not “biases.”

If we start right out by asking “What is bias?,” it comes at the question in the wrong order. As the proverb goes, “There are forty kinds of lunacy but only one kind of common sense.” The truth is a narrow target, a small region of configuration space to hit. “She loves me, she loves me not” may be a binary question, but E = mc2 is a tiny dot in the space of all equations, like a winning lottery ticket in the space of all lottery tickets. Error is not an exceptional condition; it is success that is a priori so improbable that it requires an explanation.

We don’t start out with a moral duty to “reduce bias,” because biases are bad and evil and Just Not Done. This is the sort of thinking someone might end up with if they acquired a deontological duty of “rationality” by social osmosis, which leads to people trying to execute techniques without appreciating the reason for them. (Which is bad and evil and Just Not Done, according to Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, which I read as a kid.)

Rather, we want to get to the truth, for whatever reason, and we find various obstacles getting in the way of our goal. These obstacles are not wholly dissimilar to each other—for example, there are obstacles that have to do with not having enough computing power available, or information being expensive. It so happens that a large group of obstacles seem to have a certain character in common—to cluster in a region of obstacle-to-truth space—and this cluster has been labeled “biases.”

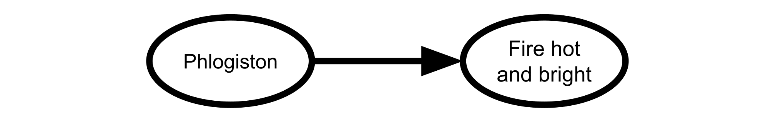

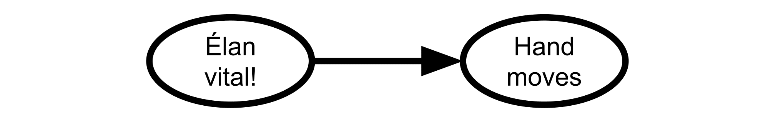

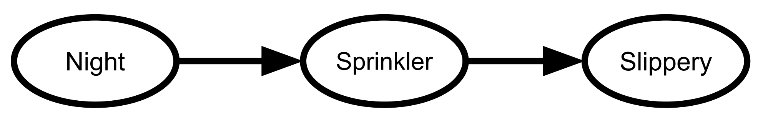

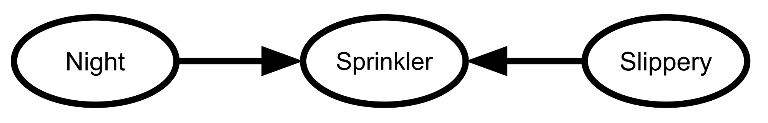

What is a bias? Can we look at the empirical cluster and find a compact test for membership? Perhaps we will find that we can’t really give any explanation better than pointing to a few extensional examples, and hoping the listener understands. If you are a scientist just beginning to investigate fire, it might be a lot wiser to point to a campfire and say “Fire is that orangey-bright hot stuff over there,” rather than saying “I define fire as an alchemical transmutation of substances which releases phlogiston.” You should not ignore something just because you can’t define it. I can’t quote the equations of General Relativity from memory, but nonetheless if I walk off a cliff, I’ll fall. And we can say the same of biases—they won’t hit any less hard if it turns out we can’t define compactly what a “bias” is. So we might point to conjunction fallacies, to overconfidence, to the availability and representativeness heuristics, to base rate neglect, and say: “Stuff like that.”

With all that said, we seem to label as “biases” those obstacles to truth which are produced, not by the cost of information, nor by limited computing power, but by the shape of our own mental machinery. Perhaps the machinery is evolutionarily optimized to purposes that actively oppose epistemic accuracy; for example, the machinery to win arguments in adaptive political contexts. Or the selection pressure ran skew to epistemic accuracy; for example, believing what others believe, to get along socially. Or, in the classic heuristic-and-bias, the machinery operates by an identifiable algorithm that does some useful work but also produces systematic errors: the availability heuristic is not itself a bias, but it gives rise to identifiable, compactly describable biases. Our brains are doing something wrong, and after a lot of experimentation and/or heavy thinking, someone identifies the problem in a fashion that System 2 can comprehend; then we call it a “bias.” Even if we can do no better for knowing, it is still a failure that arises, in an identifiable fashion, from a particular kind of cognitive machinery—not from having too little machinery, but from the machinery’s shape.

“Biases” are distinguished from errors that arise from cognitive content, such as adopted beliefs, or adopted moral duties. These we call “mistakes,” rather than “biases,” and they are much easier to correct, once we’ve noticed them for ourselves. (Though the source of the mistake, or the source of the source of the mistake, may ultimately be some bias.)

“Biases” are distinguished from errors that arise from damage to an individual human brain, or from absorbed cultural mores; biases arise from machinery that is humanly universal.

Plato wasn’t “biased” because he was ignorant of General Relativity—he had no way to gather that information, his ignorance did not arise from the shape of his mental machinery. But if Plato believed that philosophers would make better kings because he himself was a philosopher—and this belief, in turn, arose because of a universal adaptive political instinct for self-promotion, and not because Plato’s daddy told him that everyone has a moral duty to promote their own profession to governorship, or because Plato sniffed too much glue as a kid—then that was a bias, whether Plato was ever warned of it or not.

Biases may not be cheap to correct. They may not even be correctable. But where we look upon our own mental machinery and see a causal account of an identifiable class of errors; and when the problem seems to come from the evolved shape of the machinery, rather from there being too little machinery, or bad specific content; then we call that a bias.

Personally, I see our quest in terms of acquiring personal skills of rationality, in improving truthfinding technique. The challenge is to attain the positive goal of truth, not to avoid the negative goal of failure. Failurespace is wide, infinite errors in infinite variety. It is difficult to describe so huge a space: “What is true of one apple may not be true of another apple; thus more can be said about a single apple than about all the apples in the world.” Success-space is narrower, and therefore more can be said about it.

While I am not averse (as you can see) to discussing definitions, we should remember that is not our primary goal. We are here to pursue the great human quest for truth: for we have desperate need of the knowledge, and besides, we’re curious. To this end let us strive to overcome whatever obstacles lie in our way, whether we call them “biases” or not.

5

Availability

The availability heuristic is judging the frequency or probability of an event by the ease with which examples of the event come to mind.

A famous 1978 study by Lichtenstein, Slovic, Fischhoff, Layman, and Combs, “Judged Frequency of Lethal Events,” studied errors in quantifying the severity of risks, or judging which of two dangers occurred more frequently. Subjects thought that accidents caused about as many deaths as disease; thought that homicide was a more frequent cause of death than suicide. Actually, diseases cause about sixteen times as many deaths as accidents, and suicide is twice as frequent as homicide.

An obvious hypothesis to account for these skewed beliefs is that murders are more likely to be talked about than suicides—thus, someone is more likely to recall hearing about a murder than hearing about a suicide. Accidents are more dramatic than diseases—perhaps this makes people more likely to remember, or more likely to recall, an accident. In 1979, a followup study by Combs and Slovic showed that the skewed probability judgments correlated strongly (0.85 and 0.89) with skewed reporting frequencies in two newspapers. This doesn’t disentangle whether murders are more available to memory because they are more reported-on, or whether newspapers report more on murders because murders are more vivid (hence also more remembered). But either way, an availability bias is at work. Selective reporting is one major source of availability biases. In the ancestral environment, much of what you knew, you experienced yourself; or you heard it directly from a fellow tribe-member who had seen it. There was usually at most one layer of selective reporting between you, and the event itself. With today’s Internet, you may see reports that have passed through the hands of six bloggers on the way to you—six successive filters. Compared to our ancestors, we live in a larger world, in which far more happens, and far less of it reaches us—a much stronger selection effect, which can create much larger availability biases.

In real life, you’re unlikely to ever meet Bill Gates. But thanks to selective reporting by the media, you may be tempted to compare your life success to his—and suffer hedonic penalties accordingly. The objective frequency of Bill Gates is 0.00000000015, but you hear about him much more often. Conversely, 19% of the planet lives on less than $1/day, and I doubt that one fifth of the blog posts you read are written by them.

Using availability seems to give rise to an absurdity bias; events that have never happened are not recalled, and hence deemed to have probability zero. When no flooding has recently occurred (and yet the probabilities are still fairly calculable), people refuse to buy flood insurance even when it is heavily subsidized and priced far below an actuarially fair value. Kunreuther et al. suggest underreaction to threats of flooding may arise from “the inability of individuals to conceptualize floods that have never occurred . . . Men on flood plains appear to be very much prisoners of their experience . . . Recently experienced floods appear to set an upward bound to the size of loss with which managers believe they ought to be concerned.”

Burton et al. report that when dams and levees are built, they reduce the frequency of floods, and thus apparently create a false sense of security, leading to reduced precautions. While building dams decreases the frequency of floods, damage per flood is afterward so much greater that average yearly damage increases. The wise would extrapolate from a memory of small hazards to the possibility of large hazards. Instead, past experience of small hazards seems to set a perceived upper bound on risk. A society well-protected against minor hazards takes no action against major risks, building on flood plains once the regular minor floods are eliminated. A society subject to regular minor hazards treats those minor hazards as an upper bound on the size of the risks, guarding against regular minor floods but not occasional major floods.

Memory is not always a good guide to probabilities in the past, let alone in the future.

6

Burdensome Details

Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative . . .

—Pooh-Bah, in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado

The conjunction fallacy is when humans rate the probability P(A,B) higher than the probability P(B), even though it is a theorem that P(A,B) ≤ P(B). For example, in one experiment in 1981, 68% of the subjects ranked it more likely that “Reagan will provide federal support for unwed mothers and cut federal support to local governments” than that “Reagan will provide federal support for unwed mothers.”

A long series of cleverly designed experiments, which weeded out alternative hypotheses and nailed down the standard interpretation, confirmed that conjunction fallacy occurs because we “substitute judgment of representativeness for judgment of probability.” By adding extra details, you can make an outcome seem more characteristic of the process that generates it. You can make it sound more plausible that Reagan will support unwed mothers, by adding the claim that Reagan will also cut support to local governments. The implausibility of one claim is compensated by the plausibility of the other; they “average out.”

Which is to say: Adding detail can make a scenario SOUND MORE PLAUSIBLE, even though the event necessarily BECOMES LESS PROBABLE.

If so, then, hypothetically speaking, we might find futurists spinning unconscionably plausible and detailed future histories, or find people swallowing huge packages of unsupported claims bundled with a few strong-sounding assertions at the center. If you are presented with the conjunction fallacy in a naked, direct comparison, then you may succeed on that particular problem by consciously correcting yourself. But this is only slapping a band-aid on the problem, not fixing it in general.

In the 1982 experiment where professional forecasters assigned systematically higher probabilities to “Russia invades Poland, followed by suspension of diplomatic relations between the USA and the USSR” than to “Suspension of diplomatic relations between the USA and the USSR,” each experimental group was only presented with one proposition. What strategy could these forecasters have followed, as a group, that would have eliminated the conjunction fallacy, when no individual knew directly about the comparison? When no individual even knew that the experiment was about the conjunction fallacy? How could they have done better on their probability judgments?

Patching one gotcha as a special case doesn’t fix the general problem. The gotcha is the symptom, not the disease.

What could the forecasters have done to avoid the conjunction fallacy, without seeing the direct comparison, or even knowing that anyone was going to test them on the conjunction fallacy? It seems to me, that they would need to notice the word “and.” They would need to be wary of it—not just wary, but leap back from it. Even without knowing that researchers were afterward going to test them on the conjunction fallacy particularly. They would need to notice the conjunction of two entire details, and be shocked by the audacity of anyone asking them to endorse such an insanely complicated prediction. And they would need to penalize the probability substantially—a factor of four, at least, according to the experimental details.

It might also have helped the forecasters to think about possible reasons why the US and Soviet Union would suspend diplomatic relations. The scenario is not “The US and Soviet Union suddenly suspend diplomatic relations for no reason,” but “The US and Soviet Union suspend diplomatic relations for any reason.”

And the subjects who rated “Reagan will provide federal support for unwed mothers and cut federal support to local governments”? Again, they would need to be shocked by the word “and.” Moreover, they would need to add absurdities—where the absurdity is the log probability, so you can add it—rather than averaging them. They would need to think, “Reagan might or might not cut support to local governments (1 bit), but it seems very unlikely that he will support unwed mothers (4 bits). Total absurdity: 5 bits.” Or maybe, “Reagan won’t support unwed mothers. One strike and it’s out. The other proposition just makes it even worse.”

Similarly, consider the six-sided die with four green faces and two red faces. The subjects had to bet on the sequence (1) RGRRR, (2) GRGRRR, or (3) GRRRRR appearing anywhere in twenty rolls of the dice. Sixty-five percent of the subjects chose GRGRRR, which is strictly dominated by RGRRR, since any sequence containing GRGRRR also pays off for RGRRR. How could the subjects have done better? By noticing the inclusion? Perhaps; but that is only a band-aid, it does not fix the fundamental problem. By explicitly calculating the probabilities? That would certainly fix the fundamental problem, but you can’t always calculate an exact probability.

The subjects lost heuristically by thinking: “Aha! Sequence 2 has the highest proportion of green to red! I should bet on Sequence 2!” To win heuristically, the subjects would need to think: “Aha! Sequence 1 is short! I should go with Sequence 1!”

They would need to feel a stronger emotional impact from Occam’s Razor—feel every added detail as a burden, even a single extra roll of the dice.

Once upon a time, I was speaking to someone who had been mesmerized by an incautious futurist (one who adds on lots of details that sound neat). I was trying to explain why I was not likewise mesmerized by these amazing, incredible theories. So I explained about the conjunction fallacy, specifically the “suspending relations ± invading Poland” experiment. And he said, “Okay, but what does this have to do with—” And I said, “It is more probable that universes replicate for any reason, than that they replicate via black holes because advanced civilizations manufacture black holes because universes evolve to make them do it.” And he said, “Oh.”

Until then, he had not felt these extra details as extra burdens. Instead they were corroborative detail, lending verisimilitude to the narrative. Someone presents you with a package of strange ideas, one of which is that universes replicate. Then they present support for the assertion that universes replicate. But this is not support for the package, though it is all told as one story.

You have to disentangle the details. You have to hold up every one independently, and ask, “How do we know this detail?” Someone sketches out a picture of humanity’s descent into nanotechnological warfare, where China refuses to abide by an international control agreement, followed by an arms race . . . Wait a minute—how do you know it will be China? Is that a crystal ball in your pocket or are you just happy to be a futurist? Where are all these details coming from? Where did that specific detail come from?

For it is written:

If you can lighten your burden you must do so.

There is no straw that lacks the power to break your back.

7

Planning Fallacy

The Denver International Airport opened 16 months late, at a cost overrun of $2 billion. (I’ve also seen $3.1 billion asserted.) The Eurofighter Typhoon, a joint defense project of several European countries, was delivered 54 months late at a cost of $19 billion instead of $7 billion. The Sydney Opera House may be the most legendary construction overrun of all time, originally estimated to be completed in 1963 for $7 million, and finally completed in 1973 for $102 million.